The Greatest Obstacle to Democracy in Iran

By Dr. Reza Parchizadeh

The popular revolution in Iran that was sparked by the murder of the young Kurdish woman #Mahsa_Amini by the religious police of the Islamic Republic is gathering momentum across the country and gaining increasing support around the world. As such, the chances of the Islamist regime’s overthrow have never been so high.

In view of the nationwide uprising in Iran, what we need to keep in mind is that more important than the fall of the authoritarian regime is how to stop once and for all the vicious cycle of tyranny that has afflicted the nation throughout modern times.

While the revolution is going on, we need to reflect on how to facilitate Iran’s transition to democracy so that it can finally enjoy the taste of freedom and human rights, experience steady development under the rule of law, and form lasting friendly relationships with its neighbors and the wider world.

Based on historical evidence, the greatest obstacle to democracy in Iran is the centralized political structure and the concentration of power in one person, class or small group. True to its roots in the ancient Iranian political theology, the political structure in Iran has a tendency to converge around the patriarchal king who is the container of the “Godly Glow,” and as such is a demigod on earth whose command must be obeyed above any law.

By placing the king above the law, Iranian political theology leads to autocracy and authoritarianism. We can glimpse a notorious modern manifestation of that ancient concept in the slogan “God, King, Homeland” that was promoted by the Pahlavi monarchy in Iran, and which totally ignored modern, humanistic concepts in politics such as nation, democracy and human rights.

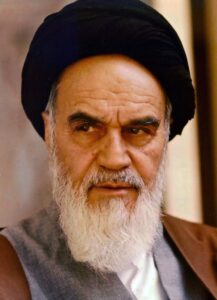

Following the fall of the monarchy in 1979, the Islamic Republic enshrined exactly the same absolutist concept in the character of a cleric. The cornerstone of the current theocracy, the “Absolute Guardianship of the Jurist,” which concenters all religious and political power in the person of the Supreme Leader, was formulated by the theorists of Shiite Islamism with a view to the classical political tradition of Iran, and only replaced the crown with the turban.

In comparison, the clergy enjoys no such absolute authority in any branch of the Sunni Islam. In Western Christianity, the power of the clerical class has been greatly reduced following several centuries of religious and political reforms, so it has been substantially democratized and mostly functions in accordance with the humanistic precepts of a secular civil society.

On the contrary, the Russian Orthodox clergy, which in many ways is a continuation of the Byzantine tradition, was historically under the authority of an absolutist tsar, and nor would it have a chance to become democratized under communism throughout the 20th century. As a result, the Orthodox clergy has turned into Putin’s instrument of oppression at home and proved a major driving force for Russia’s irredentism and imperialism abroad, similar to Shiism in contemporary Iran.

In order to rein in the historical autocracy and authoritarianism and to prevent the monopoly and concentration of power, Iranian intellectuals and political elites thought of a solution during the Constitutional Revolution of the early 20th century. When the  heterogeneous freedom fighters from the four corners of the country conquered Tehran in 1909 and deposed the autocratic Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar, in order to prevent the power from being concentrated again in the person of the king and the center of the country, at the first session of the newly-established National Assembly those visionaries introduced the “Bill for Regional and Provincial Associations.”

heterogeneous freedom fighters from the four corners of the country conquered Tehran in 1909 and deposed the autocratic Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar, in order to prevent the power from being concentrated again in the person of the king and the center of the country, at the first session of the newly-established National Assembly those visionaries introduced the “Bill for Regional and Provincial Associations.”

According to the provisions of the bill, the authority to manage many regional affairs was to be entrusted to the councils of the regions and provinces in Iran. The bill was notable in that it was the first ever attempt by the legal representatives of the people at administrative decentralization and devolution of central government’s authority to regional, provincial and local councils across the country in modern times.

If the bill had become a law, it would have laid the foundation for a decentralized government in Iran, which in the long run, by creating a multiplicity of smaller power centers, would have prevented the resurgence of centralized autocracy. For the first time in modern history, different regions of Iran would have had legally-guaranteed rights to manage their native affairs and therefore exercise a considerable degree of self-government.

However, the Bill for Regional and Provincial Associations never passed the parliament. The occupation of Iran by the Russian and British empires during the First World War and then the rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi’s dictatorship practically dismantled the constitutional system and shut down its instrument of implementation, the National Assembly, for over two decades.

More than half a century later, during the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah, under the pressure of the Kennedy administration that  expected wide-ranging democratization from Iran as a key ally of the United States in the Middle East during the Cold War, the Pahlavi autocracy finally had a now-subdued, rubber-stamp parliament pass a new version of the bill into law in 1962.

expected wide-ranging democratization from Iran as a key ally of the United States in the Middle East during the Cold War, the Pahlavi autocracy finally had a now-subdued, rubber-stamp parliament pass a new version of the bill into law in 1962.

However, by this time other forces of oppression were on the rise that would challenge the liberal law. Among the provisions of the revised bill were the enfranchisement of women and removal of the requirement to adhere to Islam to become a member of parliament. This angered Khomeini and other religious extremists to such an extent that they started a bloody uprising and forced the government to repeal the law, much to the chagrin of the Shah and the Kennedy administration.

Following the defeat of the Law of Regional and Provincial Associations in the middle of the 20th century, there were no other attempts to democratize the country by decentralizing the political structure, devolving authority and diversifying the centers of power across the nation. The Islamist revolution, with all its egalitarian claims, only led to a wholesale transfer of concentrated power from the Shah and the royal family to the Supreme Leader and the clerical establishment as well as the paramilitary guardians of the regime, the Revolutionary Guards.

Following the defeat of the Law of Regional and Provincial Associations in the middle of the 20th century, there were no other attempts to democratize the country by decentralizing the political structure, devolving authority and diversifying the centers of power across the nation. The Islamist revolution, with all its egalitarian claims, only led to a wholesale transfer of concentrated power from the Shah and the royal family to the Supreme Leader and the clerical establishment as well as the paramilitary guardians of the regime, the Revolutionary Guards.

That is, while developed democracies across the world, with the goal of further democratization, have steadily delegated different degrees of the central government’s power to the regions and provinces. Leading democracies such as Great Britain, France and Spain all enjoy a considerable degree of decentralization and devolution of authority to smaller centers of power that have enabled the people across their nations to play a more meaningful part in self-rule on a semi-macro level.

In order to finally make tyranny obsolete and turn the Islamic Republic into the last centralized and authoritarian regime in the history of Iran, it is necessary to devise and promote a scientific, comprehensive and long-term plan for the development of a pluralist discourse in Iranian society and multiplication of centers of power across the country, and this is perhaps the most important step towards the establishment of democracy in Iran.

Dr. Reza Parchizadeh (@DrParchizadeh) is a political theorist, security analyst, and cultural expert. He holds a BA and an MA in English from University of Tehran and a PhD in English from Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), all with honors. He wrote his master’s thesis on Middle Eastern history and Orientalist philosophy; and his doctoral dissertation on political thought and cultural studies in the English-speaking world, and defended both with distinction. His major areas of research interest are medieval and early modern political thought, Protestant Reformation, Renaissance Literature, British Empire, Film Studies, Middle East Studies, Chinese Studies, Japanese Studies, Russian Studies, Security Studies, and International Relations. Dr. Parchizadeh is on the editorial board of Journal for Interdisciplinary Middle Eastern Studies at Ariel University’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, the Department of Middle Eastern Studies. He is also an international committee correspondent for World Shakespeare Bibliography, the prestigious joint project of Johns Hopkins University and Shakespeare Association of America that constitutes the single-largest Shakespeare database in the world and is published by Oxford University Press. Currently, he serves on the editorial board of the international news agency Al-Arabiya Farsi.

Dr. Reza Parchizadeh (@DrParchizadeh) is a political theorist, security analyst, and cultural expert. He holds a BA and an MA in English from University of Tehran and a PhD in English from Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), all with honors. He wrote his master’s thesis on Middle Eastern history and Orientalist philosophy; and his doctoral dissertation on political thought and cultural studies in the English-speaking world, and defended both with distinction. His major areas of research interest are medieval and early modern political thought, Protestant Reformation, Renaissance Literature, British Empire, Film Studies, Middle East Studies, Chinese Studies, Japanese Studies, Russian Studies, Security Studies, and International Relations. Dr. Parchizadeh is on the editorial board of Journal for Interdisciplinary Middle Eastern Studies at Ariel University’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, the Department of Middle Eastern Studies. He is also an international committee correspondent for World Shakespeare Bibliography, the prestigious joint project of Johns Hopkins University and Shakespeare Association of America that constitutes the single-largest Shakespeare database in the world and is published by Oxford University Press. Currently, he serves on the editorial board of the international news agency Al-Arabiya Farsi.

The author of the paper may have academic credentials but lack integrity to illustrates facts according to what unfold in Iran at the time of the Pahlavi Dynasty.

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi in his book “Mission for My Country” wrote that his father wanted a political system to govern Iran’s state affair. In 1963, and not 1962, the King with the approval of the parliament passed the bill for the White Revolution. It ended the feudal system and started the welfare liberalism in Iran.

Last, the King was not an autocrat, as author is depicting the King. The left and religious factions engaged in terrorist activities and did not want to use the parliamentary system to solve the current affairs.

Thank you

Your sincerely

Peyman ADL DOUSTI HAGH