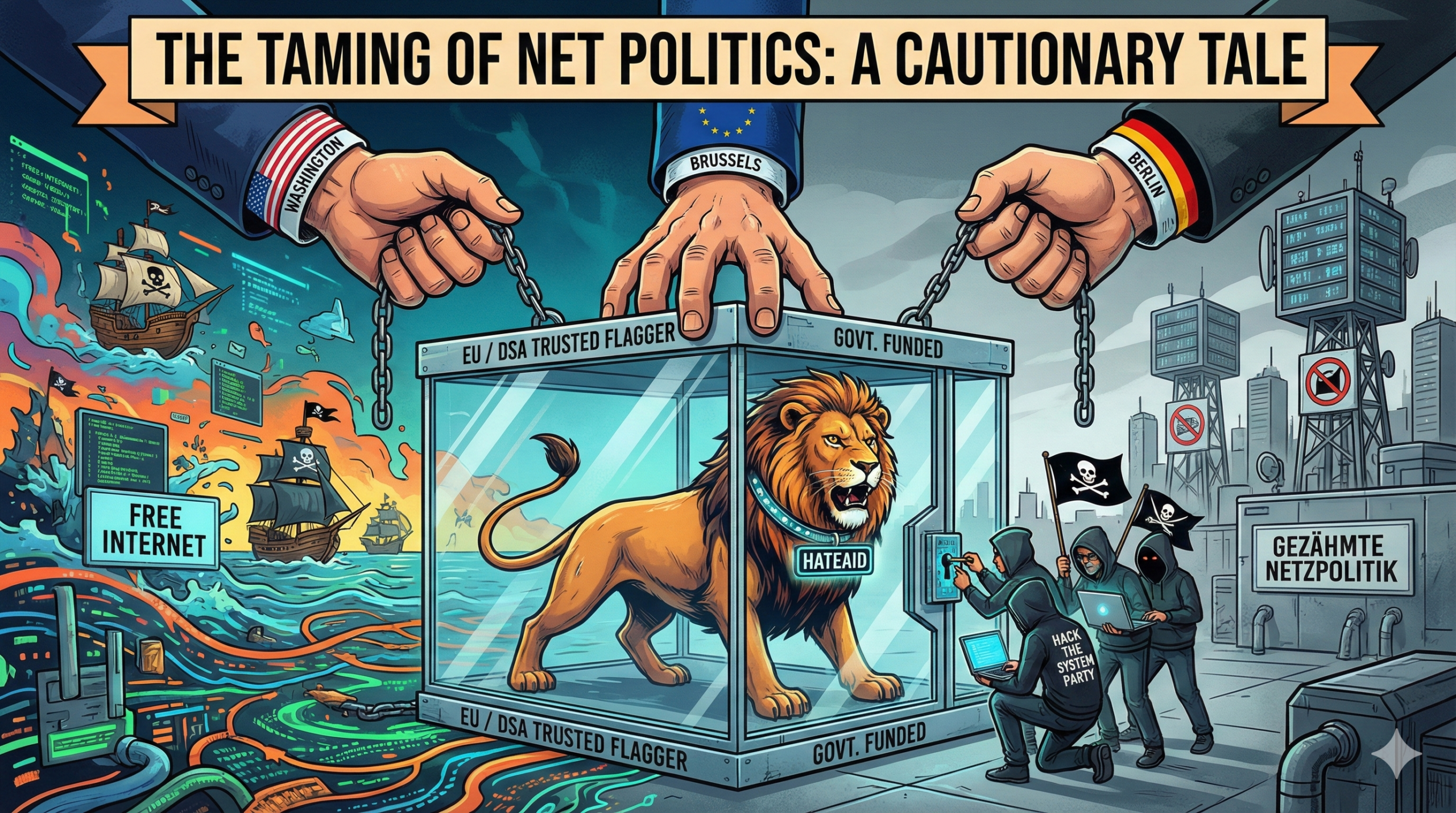

The Taming of Net Politics: HateAid as a Cautionary Tale for Digital Freedom

By Babak Tubis

The U.S. sanctions on HateAid’s leaders in December 2025 have ignited a fierce transatlantic debate. One side frames it as an attack on European digital sovereignty and the fight against online hate, while the other celebrates it as a blow against “state‑sponsored censorship.”

Both narratives, however, miss the deeper structural problem which has been emerging for years: HateAid has become a textbook example of the “gezähmte Netzpolitik” — the taming of internet politics — where independent, pluralistic activism is gradually replaced by conformist, institutionally dependent structures. This is evidenced by its state funding and privileged role as a Trusted Flagger under the Digital Services Act (DSA).

Its vulnerability in the current geopolitical crossfire is not an accident, but the logical consequence of choices made long ago. [1][2][3][11]

Crisis, Stress, and the Symptomatic Response

Overlapping crises like the pandemic and the war in Ukraine create a collective stress that heightens vulnerability to manipulation, as discussed in the lecture ‘Fakten und Fiktionen – Wie die Gesellschaft durch Unsicherheit gestresst wird,’ at the Hack the Promise Festival 2024.

Political responses often remain symptomatic: censorship that once was justified by copyright is now sold as “defence of democracy” against fake news and propaganda—a seductive one‑size‑fits‑all solution that avoids dealing with deeper causes such as diffuse fears and erosion of pluralism. This shift has led to parts of net activism being used to legitimize greater control rather than to defend an open discourse—a pattern I have observed in German net policy debates on surveillance and civil rights. [4][1]

“HateAid fits this pattern perfectly. As a state‑funded organisation with accelerated flagging privileges under the DSA’s trusted‑flagger framework, it has moved from grassroots support for victims of online violence into a semi‑institutional role inside the regulatory apparatus.”

This trend was already criticised as part of a broader willingness of net‑political actors to exchange independence for access and symbolic influence, as noted in the Tübingen talk “Digitalität und Mündigkeit.” Such institutional ties may open doors in Brussels and Berlin, but they create dependencies that make actors like HateAid a pawn in geopolitical contests between Washington, Brussels, and Berlin. [2][1]

A Self-Inflicted Vulnerability?

Please do not get me wrong! Helping people against the wingnuts on the internet is important, but the current sanctions exposed this fragility. We need to be aware of the juristic and political dangers for the public debate which can evolve by this, as Franz Josef Linder already pointed out in November 2024 on Verfassungsblog. [10]

Large parts of the German and European political establishment reacted with almost unanimous outrage, yet from a Pirate perspective, this looks like a self‑inflicted vulnerability. When activism trades its rebellious spirit for institutional integration, it becomes exposed to pressure from all sides — not only from autocracies like Russia and China, but also from allies using legal and financial levers in transatlantic disputes.

Pirate Parties International underlined the broader relevance of this critique when they republished the Basel 2024 lecture in English in July 2025. They argued that Pirate Parties must move beyond purely reactive activism toward a more reflective, mature politics that emphasises:

- Civic education and resilience.

- Pluralistic discourse instead of technocratic content control.

- The courage to tolerate contradiction without sacrificing the fight against hate. [5][1]

Reclaiming the “Forgotten Promise”

The internet’s original promise of egalitarian participation—which media scholar Tarek Barkouni described as the idea that everyone with a connection could participate equally—has largely been displaced by surveillance‑capitalist business models. Barkouni showed how early hopes were undermined first by the commercialisation of Web 2.0 and then by platforms whose core logic is advertising revenue, not democratic discourse. [6]

Meaningful change in complex systems requires precision rather than revolutionary arson. As argued at the 2025 “Hack the System – wenigstens ein bisschen” talk, we need metaphorical “hackers” who understand socio-technical systems and repair their fragility—not “arsonists” who burn everything down in the name of purity. [7]

Drawing on Kant’s call for Mündigkeit — the courage to think without external tutelage — we must reject the comfort of simple narratives and “trusted” gatekeepers. [2][6][1][8][11]

The Strategic Choice for 2026

As a member of the federal board of Piratenpartei Deutschland and the European Pirate Party (PPEU), I see this debate as a concrete strategic choice for Pirates ahead of our 2026 program renewal. Either we let ourselves be integrated as “responsible stakeholders” into flawed systems, or we rebuild an independent, uncomfortable digital‑rights movement that resists both state and corporate pressure. [3][4][1]

The HateAid case is a warning signal. Reclaiming the internet’s emancipatory promise requires emancipating net activism itself: from gatekeepers, from status‑seeking conformity, and from dogmas that confuse access with power. [1][8]

Let us hack the system — at least a little — before the system finishes hacking us.

Babak Tubis is a member of the Federal Board (Beisitzer) of Piratenpartei Deutschland, a board member of the European Pirate Party (PPEU), and active on digital rights, migration, and democracy issues.

References

- European Pirates – Board

- Wikipedia – Pirate Party Germany

- Piratenpartei Vorstand – Beisitzer

- Piraten Herne – Palantir Warnung

- PPI – Board Congratulations

- Piratenpartei Facebook

- Hack the Promise Info

- CCC Media – Digitalität und Mündigkeit

- PPI – Basel 2024 Reflections

- Verfassungsblog – Trusted Flagger

- Piratenpartei Innenpolitik – HateAid Sanctions